Hypothyroidism and Nutrition: Eating For A Healthy Thyroid

Article at a Glance

- While diet alone likely cannot cure hypothyroidism, learning about how your genetics affect hypothyroidism and adjusting your nutrition accordingly may help. Genetics account for about 70% of all autoimmune thyroid conditions. Genetic variants of interest include those of the MTRR and MTHFR genes, which affect DNA methylation.

- DNA methylation relies on enough of the right vitamins, but not too much. Scientists are still working to fully understand these interactions, but those that may affect people with hypothyroidism include B vitamins, vitamin D, selenium, iodine, and goitrogens (substances that interfere with iodine intake).

- While iodine is essential for good thyroid health, it may also be dangerous, with too much of it causing thyroid damage. Be sure not to take an iodine supplement — or any supplement — without first consulting a health care practitioner if you have an autoimmune thyroid condition.

Genes Mentioned

Contents

What is hypothyroidism?

Thyroid issues affect an estimated 300 million people worldwide. Hypothyroidism is a condition where the thyroid gland (in the neck) does not make enough thyroid hormone to properly regulate essential physiological processes. In a healthy system, thyroid hormone (thyroxine) is produced by the thyroid in response to thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), itself produced by the pituitary gland in the brain. Thyroxine is transported in the blood to regulate metabolism, growth, and development. People with an under active thyroid often experience symptoms caused by a slowing down of metabolism, including:- Feeling tired all the time

- Sensitivity to cold

- Weight gain

- Dry, cool skin

- Slow healing

- Hair loss

- Poor concentration

- Depression

- Goiter (a lump in the neck)

What is autoimmune thyroid disease?

An autoimmune condition is one where the body falsely identifies normal cells and tissues as a foreign invader and attacks them, resulting in dysfunction and disease. Autoimmune conditions include type 1 diabetes, lupus, Multiple Sclerosis, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and Graves’ disease. Graves’ disease is an autoimmune thyroid disease (AITD) where immune system dysfunction results in the production of an antibody called thyrotropin receptor antibody (TRAb). This antibody acts like thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), meaning that the thyroid gland produces more thyroxine than is necessary. This causes a dangerous increase in metabolism, leading to symptoms such as:- Rapid and irregular heartbeat

- Sweating and heat intolerance

- Tremors

- Anxiety and irritability

- Difficulty maintaining body weight

- Bulging eyes (caused by excessive tissue growth)

- Bulging neck

Nutrition and autoimmune thyroid disease

Scientists are yet to fully understand the complex interactions between genes, epigenetics, and autoimmune diseases like Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Knowing that DNA methylation is involved, however, does suggest an opportunity for nutrigenomics to modulate an individual’s risk of developing the condition. That’s because DNA methylation relies on an adequate supply of bioavailable nutrients including folate and other B vitamins. Other nutritional factors may also play a role in modulating the risk or progression of autoimmune conditions, although there is little clinical evidence to support specific interventions at this time.B vitamins

Folate, choline, betaine, methionine, and vitamins B2, B6, and B12 are needed for the production of S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe), a compound that acts as a donor for methyl groups in the process of DNA methylation. (R) As such, low levels of these nutrients in the diet can result in low SAMe synthesis and reduced DNA methylation, which appears to translate into a higher risk of autoimmune conditions. Polymorphisms that affect folate metabolism, such as MTHFR variants and MTRR variants, also affect DNA methylation and risk of AITD. (R) Ensuring a good intake of methyl donors including folate and other B vitamins, in forms that you can absorb and use, is essential for robust health throughout life. This includes supporting thyroid health and healthy immune system activity. B vitamins won’t, by themselves, cure or prevent hypothyroidism, but deficiencies of these nutrients could, it seems, raise your risk of thyroid trouble. See also: Do I have an MTHFR mutation? Here’s how to find outVitamin D

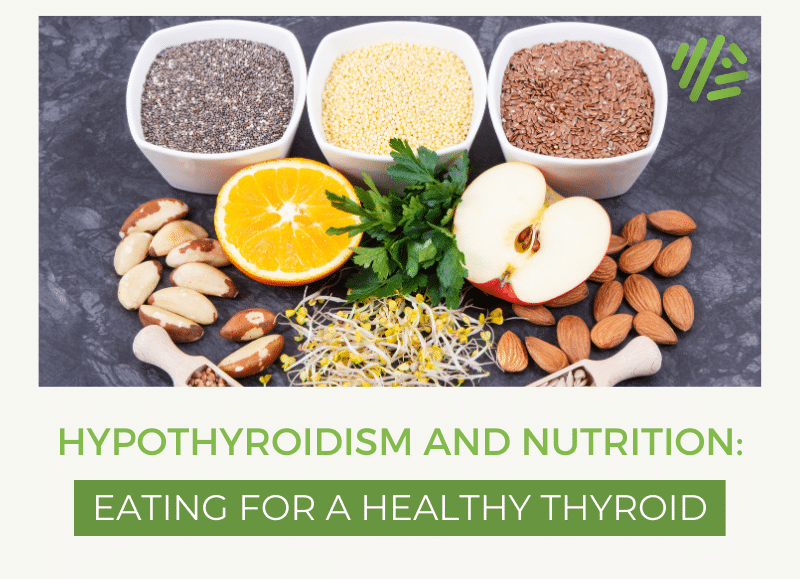

Vitamin D is another important nutrient increasingly implicated in the development of autoimmune conditions. The active form of vitamin D, 1,25(OH)2D, directly and indirectly controls the expression of over 200 genes, including several involved in immune system activity. Several studies have found that vitamin D deficiency (25(OH)D level < 25 nmol/L) is much more likely in people with AITD. In one study, 72% of people with AITD were vitamin D deficient, compared to 30.6% of healthy controls. (R) In another study, 92% of people with Hashimoto’s disease had vitamin D insufficiency (25(OH)D level < 75 nmol/L), compared to 63% of health controls. (R) As with B vitamins, taking a vitamin D supplement isn’t a foolproof way to prevent hypothyroidism, but it does seem that having low levels of vitamin D raises the risk of thyroid disease. As vitamin D is stored in the body, it’s best to have your levels tested before taking a supplement.Selenium

Selenium also plays a role in thyroid health as it is essential for the proper production of thyroid hormones. Selenium is toxic in high doses, so it’s best not to exceed 400 mcg per day. Brazil nuts are a great source of selenium and just a handful of these nuts every few days can help meet most people’s minimum need for the mineral when eaten as part of a healthy, balanced diet.Iodine

Iodine is something of a double-edged sword when it comes to thyroid health. While it is essential for thyroid hormone production, too much iodine can actually cause thyroid damage. Taking an iodine supplement without first consulting a health care practitioner could prove harmful and may even lead to hyperthyroidism and Graves’ disease. In genetically susceptible individuals, excess iodine can trigger thyroiditis. This is because highly iodinated thyroglobulin is more immunogenic than poorly iodinated thyroglobulin. Iodine may also be directly toxic to the thyroid, causing damage via free radicals and immunogenic activity. (R) Most people in North America get enough iodine from dietary sources, with two key exceptions: anyone eating a predominantly plant-based diet (which is often low in iodine) and anyone who is pregnant (because pregnancy increases iodine demands to fuel fetal growth). Many multivitamin and mineral formulas, as well as formulas featuring seaweeds (such as kelp), and those formulated to support skin, hair, and nails, often contain iodine. As such, it is important that individuals tally the total amount of iodine in all supplements they’re taking, as well as likely intake from dietary sources including iodized salt and seaweeds, as well as medicines such as amiodarone and some topical antiseptics and contrast dyes. Anyone taking thyroid medications needs to be especially careful about natural supplements that may contain iodine as this may interfere with the effectiveness of medications.Goitrogens

Just as certain nutrients help support thyroid health, some dietary constituents can hinder thyroid function. Goitrogens are foods or substances that interfere with iodine uptake in the thyroid gland, leading to reduced production of thyroid hormones. Common goitrogens include:- Bok choy

- Broccoli

- Brussel sprouts

- Cabbage

- Cauliflower

- Kale

- Kohlrabi

- Mustard and mustard greens