Can Undigested Protein Contribute to Leaky Gut?

Contents

At Gene Food, we spend a lot of time thinking about why a given diet might work for one person, but might not work for their neighbor down the street. To this end, one of the topics we’ve been very interested in lately is protein metabolism and digestion.

Let’s picture a nice sunny July day. A number of friends and neighbors have gathered to celebrate the 4th of July. The beer is cold and the barbecue is hot. What’s on the menu?

BBQ chicken.

The fascinating part for us as nutrition nerds is how the different guests at the party will metabolize the chicken they eat. In the ideal scenario, guests at the party digest and assimilate all of the nutrients in the chicken through the small intestine after the proteins are broken down by the stomach. But as we will learn in this post, when we eat more protein than the body can digest, undigested protein makes its way to the colon where it doesn’t belong and where it can wreak havoc on our gut health. 1

Let’s dive in to discuss the possible differences and how that second helping of chicken may cause digestive and mood issues for some of the guests while helping others at the party pack on muscle.

Personalized nutrition and protein

The personalized approach to protein digestion recognizes that:

- Not everyone is born with the same ability to digest protein

- Not everyone is born with the same ability to deal with the waste products of protein digestion

This isn’t conjecture, it’s been proven by extensive scientific research.

Hydrochloric acid and blood type

In a previous blog post on the largely debunked blood type diet, we highlighted research showing that different blood types have different levels of hydrochloric acid (HCL) in their stomachs.

Blood type O tends to have the most HCL, while type A tends to have the least.

Since our body’s use HCL to digest protein, changes in HCL, whether genetic or due to lifestyle, play a role in how much protein we can handle.

Protein waste products

Similarly, urea cycle function, essentially the janitorial crew of protein digestion where the body gets rid of protein waste, varies by individual.

Because ammonia is the end waste product after the body breaks down the organic nitrogen in protein, children born with no urea cycle function rapidly see toxic levels of ammonia accumulate in their blood. Harvard’s health blog has speculated that the extreme case of zero urea cycle function could be a clue for highly variable urea cycle function, with some of us much better suited for high protein diets than others.

Horizon Health, a biotech startup, maintains a website devoted to urea cycle disorders where readers can take a quiz which is designed to help them gauge whether their ammonia levels could have reached unhealthy levels due to an excess of protein consumption.

Protein digestion 101

Thus far, we have learned that personalized nutrition encompasses differences in protein metabolism.

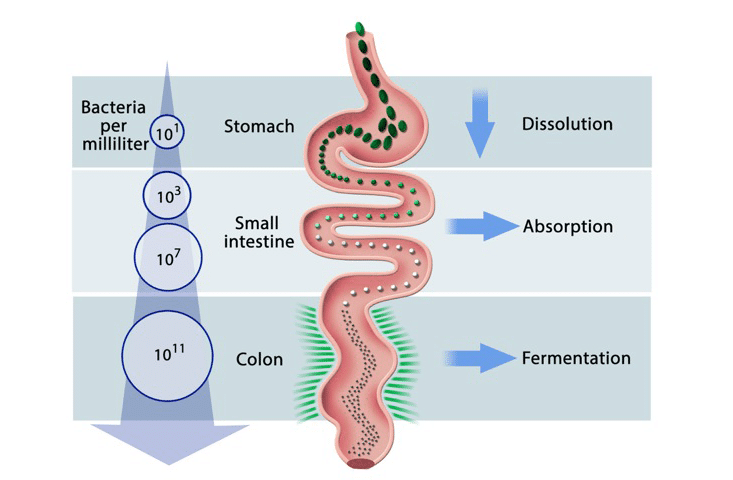

What are the basics of protein metabolism that we all share? The chart below, created for this excellent Nautilus article provides a nice visual of the various stages.

For our example here, let’s say I just ate a piece of that mouth watering BBQ chicken.

What happens next?

- Hopefully, I remember to chew

- The chicken then makes it way to my very acidic stomach where the protein is dissolved

- HCL and pepsin in the stomach breaks protein down into different amino acids 2

- The pulverized chicken becomes “chyme” and heads to my small intestine

- The chyme reaches the small intestine where digestive enzymes and bicarbonate neutralize the acidic PH of the HCL for the absorption phase

- Amino acids and peptides are “liberated” as the chyme is digested by the small intestine

- The amino acids make their way across my intestinal wall into the blood stream where they are used for building new proteins

- If I’ve eaten more amino acids than my body needs, they convert to glucose

- The nitrogen waste liberated by this process is turned into ammonia and dealt with by the urea cycle

What if we eat too much protein?

This question is part of the reason I wrote my blog post on why the Carnivore diet is unhealthy for most people. There is a mountain of evidence that an excess of protein can lead to a series of disease states.

Dr. Valter Longo, head of longevity at USC, and creator of the fasting mimicking diet, has spent his career describing how certain pro-growth, but also pro-inflammatory amino acids, found in greater abundance in animal protein, such as lysine, methionine, and the branch chain amino acids can turn on our cancer pathways.

I would highly recommend reading Dr. Longo’s book and his published research, however, the rest of this post will focus on how an excess of protein can affect the microbiome.

Undigested protein and the microbiome

Here’s a scenario for you: remember that chicken we were eating a minute ago? Who is to say you digested it perfectly? Perhaps some of the amino acids made their way to the bloodstream for tissue repair, but maybe a few ounces remained largely undigested and made its way to the colon.

Remember, the colon is responsible for the fermentation stage of digestion. When undigested protein leaves the small intestine and enters the colon, we have an issue. As the chart above teaches us, the job of the colon is to ferment complex carbohydrates. The colon uses fiber to make short chain fatty acids, like butyrate, that the body uses for energy and as a protective lining which keeps the gut healthy. 3

So, yes, we want our morning oats to ferment in the colon, but no, we probably don’t want our BBQ chicken to ferment in the colon. At this point, you may be asking: is this even possible? Can the meat we eat ferment in the colon?

Unfortunately, yes, it is possible, but only when we are eating more protein than our bodies can break down and digest. The question becomes what is the health impact for someone who, for example, is on a high protein, low carbohydrate diet for weight loss, but who also has diminished ability to digest protein? This is a question the scientific community is working to better answer.

To quote a recent review in the Journal Microorganisms:

In the case of high-protein weight loss diets, protein intake may be 2–5 times greater than the daily dietary recommendations. Understanding the fate of undigested dietary protein is an important consideration in determining the effects of long-term dietary patterns on health.

Some of our more astute readers may be asking – doesn’t undigested protein also ferment in the colon producing butyrate? Yes, this does happen, but fermenting protein produces far less short chain fatty acids than does fermenting carbohydrate. In an ideal world, none of the protein we eat makes its way to the colon, it is all absorbed and used in the small intestine. Fermenting protein produces ammonia and amines that are bad for our gut health. It also rapidly changes the species of bacteria in the gut from the good guys who feast on complex carbohydrates, to the bad guys who produce more ammonia and that inflame the bowel.

Fermenting protein stimulates the growth of these pathogenic species of bacteria in our gut:

- Alistipes,

- Bilophila,

- Bacteroides

These additional characters produced by fermenting protein are thought to damage the lining of the gut, which can contribute to leaky gut, a disease state where the barrier of the colon becomes permeable allowing undigested food and other particles into the bloodstream that don’t belong there.

Key takeaways

The purpose of this blog post is not to suggest that every last piece of chicken we eat at a summer barbecue ends up rotting in our colon. In the normal scenario, small portions meat are easily digested and assimilated in the small intestine and never get to the colon.

However, it is each individual’s responsibility to understand the factors that allow for a personalized approach to nutrition. One of those factors is HCL levels, another is urea cycle function. Absent testing for either of these variables, a simple blood test to measure ammonia levels could be helpful.

The goal is to eat meat your body can use. Overwhelming the system with loads of protein it can’t use or digest can have long term health consequences for some individuals.